The 1990s movement for teaching English through communicative approaches shifted the focus from rote learning and daily drilling to thinking about language acquisition. Linguists began to investigate how learners could use their language skills to communicate more naturally rather than mechanically repeating chunks of memorised speech patterns. Rote learning created decontextualized learning that learners had difficulty applying to real life situations outside the classroom. Krashen (1980), hypothesised that new language learners are able to naturally “acquire” languages through continuous interactions and exposures to the target language.

So what does this mean for our newly arrived EAL students? Do we begin with focussing on communication rather than the forms of the English language. Let’s dig a little deeper into this idea of language acquisition.

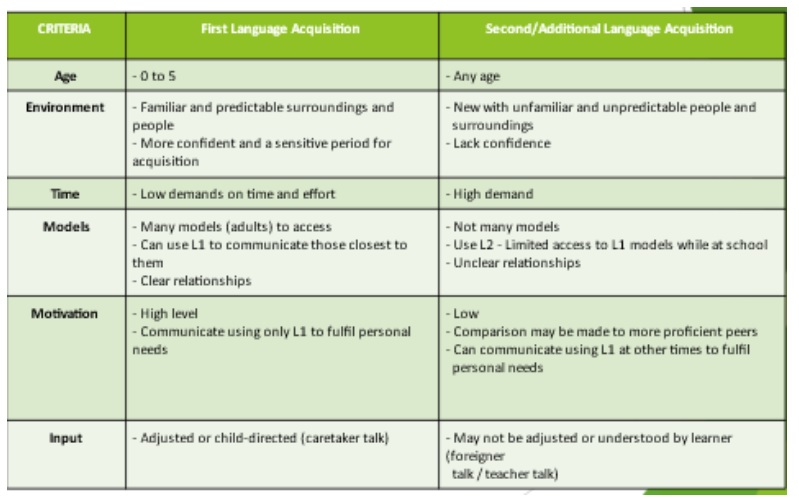

We can look at language acquisition through the five criteria of age, environment, time limits, access to models, motivation, and input. From the table above, we can see that first language acquisition happens between the ages of 0 to 5 in a familiar and predictable environment. There is very little demand on time and effort and we often adopt the mindset of “every child learns at its own pace”. On top of that, there is access to numerous adults or models with clear relationships. At this age intrinsic motivation is at its all high as all communication is to fulfil personal needs. The adults around the learner adjust their talk to encourage learning. For example, if a child says, “Yesterday, I eat apple”, the adult would most likely repeat, “Oh that’s nice, you ate an apple yesterday”. We don’t directly correct the learner. Let’s compare that to a second or additional language learner:

Acquisition happens at any age – most of our newly arrived refugee students are older than five but are acquiring their additional language for the first time.

They are in unfamiliar and unpredictable territory – scary for anyone at any age.

We put very high demands on their time – in Australia, they are given a limited amount of time from their date of arrival to moving into a mainstream classroom. This can vary between 12 to 24 months depending on the state they are in. They spend this time in language centres and schools scrambling to get from zero to some English before they are expected to put in extra effort and perform alongside first language Australian students. These students are expected to sit for culturally exclusive national exams although multiple research shows that it takes many years for a new learner to reach native speaker levels. In some countries, refugee and migrant learners are immediately placed into mainstream classrooms and expected to learn the new language.

They don’t have access to many models. Often, their families are also new to English. Therefore, their only models may be teachers and peers with whom they may have unclear and sometimes difficult relationships.

There is a lot of outside pressure and comparison to more proficient learners. This can be detrimental to the learners’ motivation to continue learning a language in the language they are learning.

We may not adjust our talk to make it more comprehensible to the learner.

Finally, it may be crucial for us to consider that most of us learn a new language out of a personal choice but most of our EAL students are forced to learn an additional language although they may already be multilingual due to situations that they could not control. Knowing the difference between language acquisition and language learning may help us determine what we are presenting to our students.